The God of Borders

Current headlines make border disputes and migration seem like uniquely modern issues. However, two researchers at Freie Universität Berlin show that these phenomena are much older than we might expect.

Feb 03, 2026

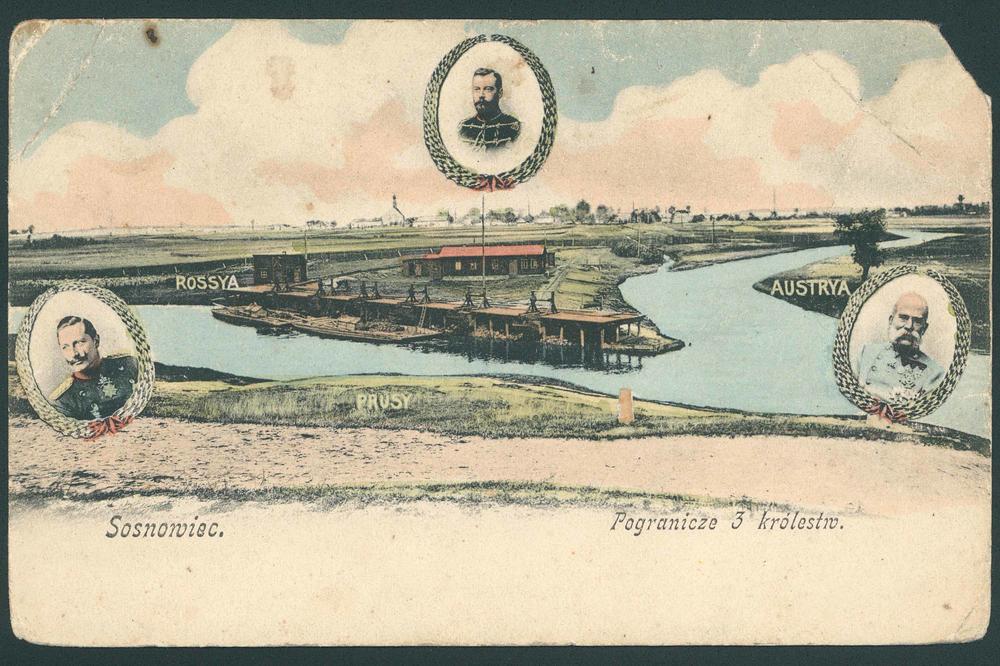

Three Emperors’ Corner, a former triple border at the confluence of the Black and White Przemsza rivers, depicted on a postcard dated sometime before 1914. It is located near the towns of Mysłowice, Sosnowiec, and Jaworzno in present-day Poland.

Image Credit: Biblioteka Narodowa, Warsaw

According to Dr. Jens-Olaf Lindermann, many altars, including a shrine to Terminus – the Roman god of borders – once stood on Rome’s Capitoline Hill. When it was decided that they should be moved and a temple to Jupiter built in its place, the augurs took the auspices to discover whether the god or goddess of each altar was content for it to be relocated. Terminus was the only god who refused permission. The stone was therefore included within the new temple, and its immovability was regarded as a good omen for the permanence of the city’s borders. In his Fasti, the ancient poet Ovid attributes the foundation of peaceful Roman coexistence to Terminus.

Lindermann is a Latinist and scholar whose main interest lies in textual criticism. He was an assistant professor in the TOPOI Cluster of Excellence at Freie Universität for many years and is currently working on his professorial teaching qualification (Habilitation). Until recently, he was involved with several research projects funded by the Gerda Henkel Foundation. His research deals with land surveying in Roman times, and how boundaries were drawn and land divided.

Divvying up the Land

To understand the Roman approach to land surveying, it is important to know that their aim was to create order and establish clear legal boundaries. Land surveyors were considered the intellectual spearheads of Roman conquest and a fundamental part of the incorporation of larger and larger parts of Italy, Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Near East into the Roman Empire. Every street, military camp, or city was only possible once agrimensores, gromatici, or finitores – the Latin terms for a land surveyor – had measured the land, rendering it something that could be divided and therefore controlled.

Together with Eberhard Knobloch (Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities) and Cosima Möller (Freie Universität Berlin), Lindermann has published critical editions by central authors from the Scripta Gromaticorum Romanorum, a compilation of treatises on land surveying from extant manuscripts. The Arcerianus, a manuscript from the fifth and sixth centuries C.E. now housed in the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel, is the earliest of these manuscripts. They are highly technical works, often difficult to understand for the scribes who copied them and had no special understanding or knowledge of land surveying. Nevertheless, they formed the foundation for all mathematical and surveying knowledge throughout the European Middle Ages.

During his research, Lindermann discovered that the history of Roman land surveying literature partially needs to be rewritten, especially with regard to one of the central gromatic authors. He redates Julius Frontinus to a later period than previously thought and distinguishes him from his namesake, the consul Sextus Julius Frontinus, with whom he had long been confused.

The surveyor Hyginus wrote, “Among all the tasks of surveying, the marking of boundaries is the most important, for it is of divine origin and lasting significance.” The boundaries that Hyginus refers to could be of three types: between private properties, between individuals and state-owned land, or those drawn by surveyors in newly conquered territories when the lands were measured and parceled out for the first time.

Dr. Jens-Olaf Lindermann was involved in the edition project “Die gromatischen Traktate des Iulius Frontinus” (“The Gromatic Treatises of Julius Frontinus”), funded by the Gerda Henkel Foundation.

Image Credit: Personal collection

In Latin, there are several words for “boundary:” limes, finis, and rigor. They each have different meanings, but none of them refers to a political border between states as we know it today. The Roman Empire itself did not have clear-cut borders; rather, its zones of influence tended to simply diminish and fade at the edges. Lindermann calls these “fuzzy borders,” using a term coined by a research group led by Friederike Fless and Stefan Esders. These fuzzy borders are the reason why there were no physical barriers, no passports, and none of the border regimes that would eventually emerge much later in European modernity.

Political and Physical Borders

Dr. Franziska Exeler, an expert on Eastern European history, is researching precisely how these border regimes came into being, including what forms they took and what forces were at work during their development. Exeler is a research associate and lecturer at Freie Universität Berlin’s Friedrich Meinecke Institute. She believes that the region in Upper Silesia (German Empire), Małopolska (Russian Empire), and Galicia (Austria-Hungary) where three imperial borders met at the “Three Emperors’ Corner” served as a laboratory for the development of modern border regimes as we know them today.

The intersection of the three imperial powers brought to the fore a system of citizenship, political borders, travel documents, and border checkpoints that both enabled and restricted crossing state lines, a system that has continued to this day. “In the nineteenth century, we see European states developing their statehood by conquering colonies while at the same time introducing measures to standardize how the empire was run internally,” explains Exeler. “We see how internal borders disappeared, as was the case after the North German Confederation was founded in 1867 before it was succeeded by the German Empire in 1871. Over the course of the century, the internal political space would become more unified, shifting the importance of borders outward. This included customs borders, which previously often ran between different regions.”

The second half of the nineteenth century is often described by historians as an era of relative freedom of movement within Europe. However, Exeler points out that this image only really applied to certain parts of Western and Central Europe. In the region she studied, where the Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian empires converged, the borders were both heavily controlled and somewhat porous. Exeler says that this conflicting tension between restriction, openness, and the attempt to steer migration still shapes European borders today, even within the European Union.

Dr. Franziska Exeler is a research associate and lecturer at Freie Universität Berlin’s Friedrich Meinecke Institute

Image Credit: Personal collection

“Along the border where Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Prussia met, we can observe a trend in the second half of the nineteenth century that was part of a worldwide phenomenon: namely, the tendency of states to regulate labor migration based on ethnicity,” Exeler explains. “In the United States this led to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, while in East-Central Europe this largely concerned the labor migration of Polish-speaking people from the Russian Empire and from Galicia, the northeastern part of Austria-Hungary. Under pressure from Prussia, this migration was heavily regulated and restricted.”

Migration, and the attempts to control it, only became possible because serfdom was abolished in the first half of the nineteenth century, and because freedom of movement was allowed within the North German Confederation. This led to many farmworkers from the eastern provinces of Prussia moving to the western Ruhr region, where the mining industry proved much more lucrative than farmwork.

However, this upsurge in migration soon created a shortage of labor back in Prussia’s eastern provinces, especially on the large agricultural estates. To counteract this, Prussia wanted to attract cheap laborers from Galicia and the Kingdom of Poland (then under the rule of the Russian Empire); however, it also wanted to make sure that these workers did not settle permanently, start families, and have children.

Migration Remains Relevant

Exeler’s examination of the Three Emperors’ Corner serves as a microhistory of modern border regimes. She defines four types of migration that defined the region: agricultural (i.e., the east‑west migration of seasonal laborers into Prussian agricultural contexts), transatlantic (i.e., emigration to America, primarily from the Russian Empire); illicit trade and sexual trafficking (i.e., the illicit smuggling of goods and women); and coal mining (labor migration to the Russian‑Polish black coal industry from Upper Silesia and Galicia into the Kingdom of Poland).

It is striking how many of these past developments continue to resonate in today’s debates about migration, border openings, and border closures – even though Terminus, the god of borders, has long since faded from memory.

This article originally appeared in German in the Tagesspiegel newspaper supplement published by Freie Universität Berlin on November 29, 2025.